Network and Security Design

Veröffentlicht: 26.08.2024 | Bearbeitet: 26.08.2024 | Autors: Thomas Liske, Marcel Koch, Tassilo Tanneberger, Matthias Wählisch

In the second article of our series “IXP from Scratch”, we introduce network and security design decisions as well as implementations we made at DD-IX, an Internet Exchange located in the city of Dresden, Germany. In principle, an IX consists of a single broadcast domain, but in practice an IX has to operate several services securely to provide reliable peering services to its members. |

Services of IXP operations

An IX provides external and internal services for peers and members. At DD-IX, all services run on our own hardware, except for e-mail, web conferencing, and Matrix chat. The latter ensures that communication is not impaired in the event of faults or attacks on our infrastructure. We favour providers who offer exclusively open source-based solutions.

The most important services are currently,

to manage IXP services

* IXP Manager - that was to be expected, wasn’t it? * Alice-LG - our friendly looking glass for the route servers

to manage our network

* Netbox - as IPAM and DCIM solution, not used for automation * Grafana & Prometheus - for observability and alerting

to manage our daily office work

* Nextcloud - with OnlyOffice and draw.io integration * Vaultwarden - our password manager * Mailman3 * for community mailing lists (e.g. DDNOG)

User authentication and authorization

From the beginning, it was clear to us that we needed a central identity provider (IdP) for user authentication and authorizations. This separates user authentication from services, and login credentials are only processed at the IdP. A compromised single service would thus not leak any credentials or sessions of other services connected to the IdP - except if the IdP itself is exploited. The IdP is therefore the most important service in terms of availability and security. We have decided not to use a cloud-based IdP, because we dont out-source security.

We encourage our users to use passwordless WebAuthn-based authentication with user verification and require 2FA for password-based login as a fallback.

At the beginning, we used Keycloak as IdP. While Keyclock is very flexible and almost feature complete, it requires a lot of configuration and does not support RADIUS. We later changed to Authentik because it is more lightweight and provides a RADIUS Provider, which we use to authenticate on network devices.

Selecting the Right Platform for your Services

How do you want to operate all these services? A single server to rule them all? Just a bunch of VMs? K8s? your level of distribution? And then you have to decide whether you treat your servers as Pets or Cattles 😉.

Those questions are not easy to answer and depend not only on the computer resources available, but also on the knowledge (and habits) of the staff operating the IX. At DD-IX, these deliberations influenced our choice of software, which we would like to highlight in the following sections:

NixOS, a home for our administrative services

NixOS is a Linux distribution in which the entire system configuration and the packages are described by the domain-specific language (DSL) nix. In addition, NixOS also provides features such as atomic rollovers, rollbacks, and strong reproducibility. However, describing a system configuration with a functional DSL like nix requires a lot of training.

Alpine Linux, a home for our network infrastructure components

Alpine Linux is a Linux distribution that supports diskless operation. Running the operating system completely in RAM brings the following advantages. First, it is more sustainable because RAM is less impacted by ageing compared to frequrently used disks. Second, any misconfiguration that breaks the system is resolved by a reboot since the system does not keep persistent states. These properties make Alpine Linux well-suited to run network services such as routers, route servers, and firewalls. The frequently changing parts of the configuration, e.g., BGP configurations, will be loaded during runtime to not conflict with an always operational base system.

Ansible

Having the two operating environments NixOS and Alpine Linux we still need some glue for cross-system automation. For this, we use Ansible, which is executed on NixOS to repeatedly reconfigure our Alpine Linux-based route servers and Arista EOS-based peering switches.

Service isolation

We isolate all services using hypervisors to minimise the risk of lateral movement in case a service is exploited. It may sound like a lot of effort to run all services in dedicated virtual machines, but it is not if the concept of MicroVMs is used. The fundamental idea of MicroVMs is to put each services into dedicated VMs, similar to containers. These VMs avoid the emulation of common hardware but rely on a large extent on VirtIO drivers to minimize the virtualisation overhead.

At DD-IX, we decided to use NixOS with Astro’s microvm.nix. This setup only takes a few additional nix-config options to put a service into a microvm.

The NixOS store of the base system is mapped read-only into the microvm containers using the virtiofs filesystem, which results in almost no storage overhead compared to a single machine setup. With the exception of memory and IP addresses, all resources can be shared efficiently with this setup. We make our nix-config publicly available.

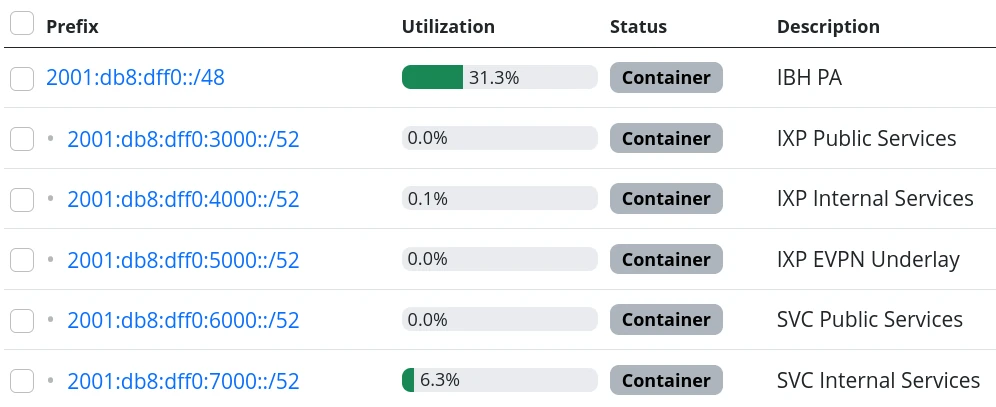

Addressing Scheme

We decided to use IPv6 addressing for all internal and external services. Of course, we also assigned a small number of legacy IPv4 addresses to our public services. We got an /48 IPv6 prefix which allows us to use 16 bits to encode organizational aspects in the prefixes based on our network segmentation.

The advantage of this scheme is that we can recognise the associated zone from the network ID of an IPv6 address without consulting our IP address management tool (Netbox). It is, therefore, much easier for people to work with IPv6 addresses than with IPv4 addresses 😎.

How hard can IPv6-only be?

Originally, since we started with a greenfield deployment, we were optimistic deploying an IPv6-only network internally. This should be possible in 2024, shouldn’t it?

We have failed several times to deploy an IPv6-only network. There are still leaf switches being sold whose silicon can not provide all features in IPv6 (underlays). The switch model we use have been launched around 2018, and so we have IPv4 addresses in our MP-BGP EVPN underlay. What we did not expect was that our core software (NixOS, IXP Manager, and arouteserver) requires also IPv4. Unfortunately, the NixOS infrastructure relies heavily on GitHub and, even in 2024, GitHub still does not provide AAAA resource records for github.com. Some of the online lookups that our IXP tool chains perform are still offered only via IPv4.

We looked at the available IPv6-only transitions. All transitions use some NAT(-like) mechanism which are not implemented in the vanilla linux kernel running on our firewall and for some of the transitions we would need to tamper recursive resolution inside of our network. We do not like any kind of NAT and we don’t like tampering.

We have therefore decided to still use IPv4 addresses in VLANs, but only if it is required. The non-public VLANs use an RFC1918 setup with NAT, we can’t have everything.

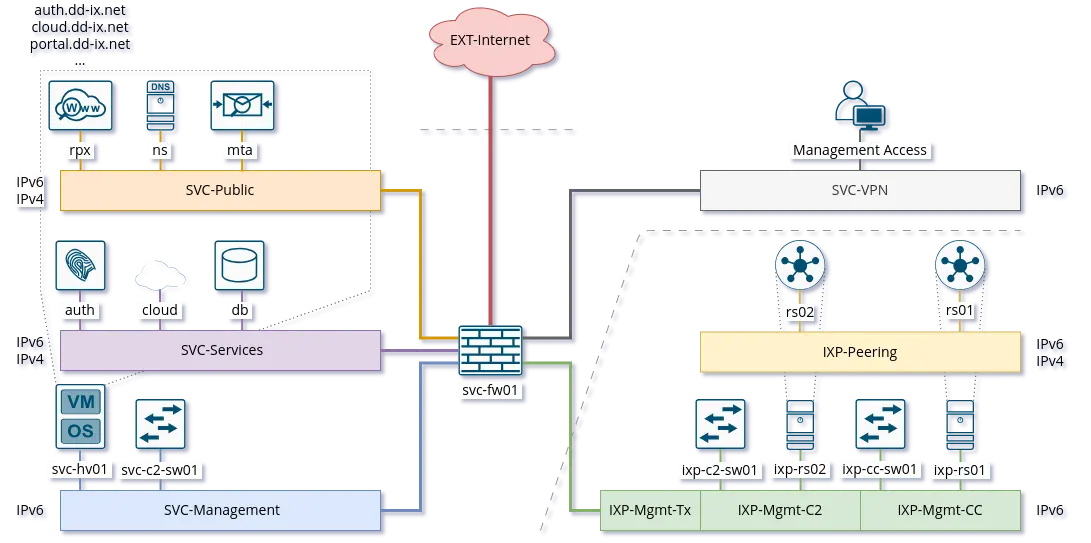

Network Segmentation

We base the segmentation of our network on a very lean model. Every microvm is attached to a single broadcast domain, implemented using VLANs. The VLANs are logically grouped into security zones.

Devices, VMs and VLANs are always assigned to exactly one zone and have no direct connections outside of their zone. Of course our firewall is an exception to this rule, intentionally. The firewall is the only device attached to the external zone gate keeping any of the other zones.

But which service goes into which zone? We make the assignment based on three differentiations.

Security Zones

The “IXP” zone contains all devices and services that are directly attached to the peering LAN. This includes dedicated switches for the peering lan and connected route servers.

The second and largest zone “SVC” contains all devices and services that are necessary for the association and its business operations.

In the future, we are also planning to have a “LAB” zone for a full-stack IXP testing environment.

Usage

This is a somewhat vague definition and should contain from where can this service be accessed and to which application tier does the service belong to (if applicable)? A Web application such as the IXP Manager uses three services, each of them assigned to a different zone:

* SVC-Public - our reverse proxy making the service public accessible * SVC-Services - the application server where IXP Manager runs * SVC-Backends - a database at our backend database service

Distinguisher

If we require more than a single VLAN within a zone a distinguisher is appended. This might be a counter or a location abbreviation. At the moment only the IXP zone is distributed over more than one PoP and we avoid to have PoP spanning broadcast domains if appropriate. So while the peering LAN is spanned over all PoPs the management and quarantine VLANs are of course not and so their name need to get distinguisher appended.

Defining zones helps to get some criteria for a more objective decision on which services should be separated from others.

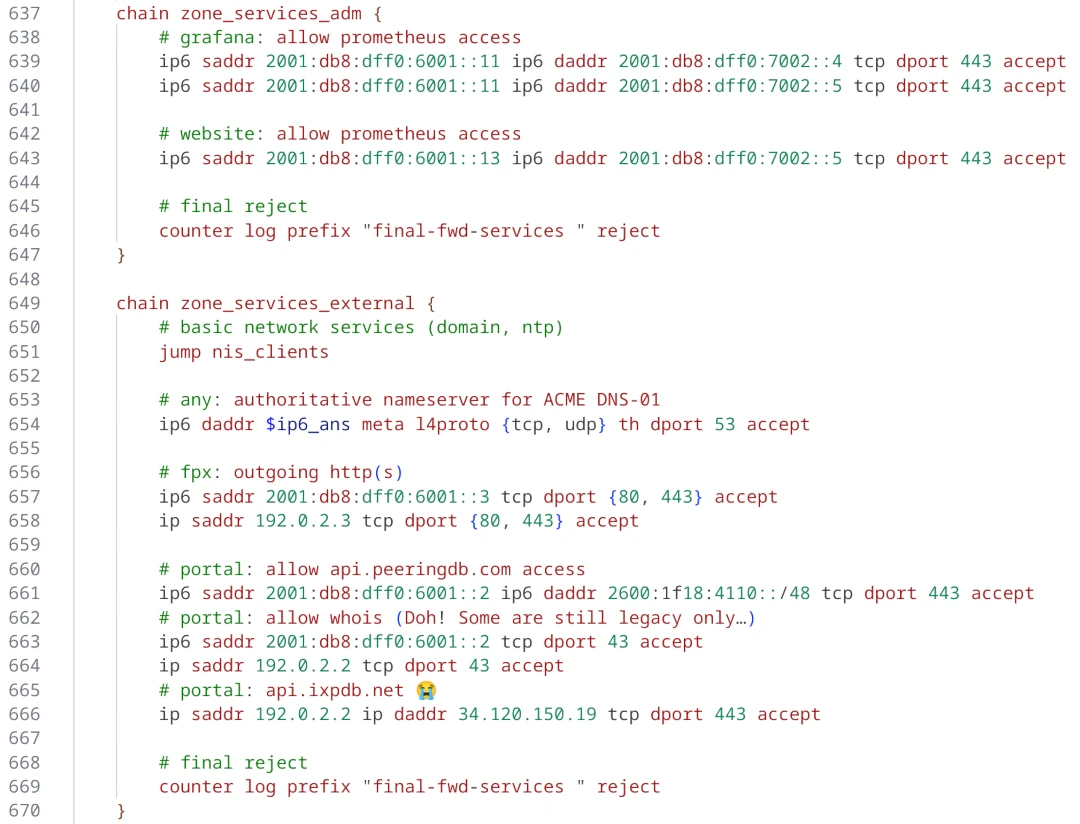

Firewall & Routing

We use a stateful firewall to apply a restrictive ACL-based policy when routing between the security zones. The firewall is based on nftables, which provides a more comprehensible firewall implementation compared to the older iptables and netfilter approach. Another advantage of nftables is that it allows to write dual stack access rules - this releases us from keeping additional legacy IPv4 rulesets in sync.

Using large linear ACLs may introduce the risk of becoming inefficient and hard to understand with evolving deployment. Splitting the ACL into sub-ACLs based on security zones or interfaces allows to avoid this drawback. This approach is usually supported by most firewall solutions and we follow these simple rules:

Split the access rules into sub-ACLs for each tuple of source and destination zone.

A sub-ACL always enforces a final decision: they all should have a final

deny any anyrule.The inbound and outbound interfaces allow to map the corresponding source and destination zones.

From the main ACL, the corresponding sub-ACL is only called based on the zone tuple.

The sub-ACLs are named and ordered by the source and destination zone in the ruleset file for reasons of clarity.

This adoption of divide and conquer principle makes it easy to maintain even large firewall policies. To add or find a rule, we only need to know the source and destination zones to locate the corresponding sub-ACL, which is usually very easy to understand. One additional advantage is that there is a much lower risk of writing rules that allow for more than intended.

Conclusions

Planing the server infrastructure and network to run your IXP is not always obvious. Before you start, do not forget:

Explicit rules about operating your infrastructure are helpful. Decide on a strategy, stick to it, and reconsider after some time, instead of deciding every case separately.

Categorize your services. It will ease the design of security and reliability concepts.

There is more than “Linux”. Declarative operating systems might be suitable for common services and provide the advantages of structured testing. Services that require quick and easy reset in case of misconfiguration benefit from diskless operating systems but require highly automatic configuration to reinitialize valid states. Pick the Linux distribution that fits best your predefined rules.

Isolate your services on multiple layers.

IPv6 is still not supported on every platform, neither hardware nor software that you run, or services provided by third party 😭. This does not mean, however, that you should design your network based on IPv4. In fact, you should consider IPv6 as the default and allow IPv4 only where absolutely necessary, otherwise we will not make progress with overdue changes.